Global Conflict Trends

Assessing the Qualities of Systemic Peace

Perhaps, the most important, and challenging, task for the peace researcher is to establish and maintain a systematic perspective on the general condition of peace in the global system. Without that, progress toward the greater peace cannot be accurately gauged and policies cannot be properly evaluated. Measuring systemic peace is a necessarily holistic endeavor. The quality of peace cannot be improved simply by displacing violence and war to a different setting or separate category, or by concentrating misfortunes with the less fortunate (i.e., ghettoization).

Complex societal-systems challenge our comprehension but, with recent advances in information resources and computation technologies, systems can be reliably monitored. The ending of the Second World War in 1945 provides a good beginning point for measuring and tracking changes in the global, systemic qualities of peace. The following charts comprise information on all countries in the world with populations greater than 500,000 persons in 2018 (167 countries in 2018). Regional trends are examined in the suites found at the bottom of the "figure accordion" following.

04  |

05  |

06  |

07  |

08  |

09  |

10  |

11  |

12  |

13  |

14  |

15  |

16  |

17  |

18  |

19  |

20  |

21  |

22  |

23  |

24  |

Click each link in the "figure accordion" below to examine one of the above listed perspectives on the global quality of systemic peace.

Click on the diagram for that perspective to view it as a larger image.

-

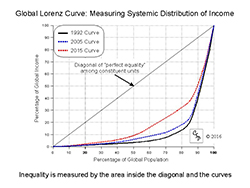

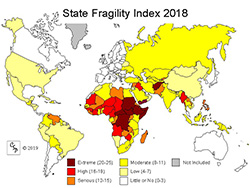

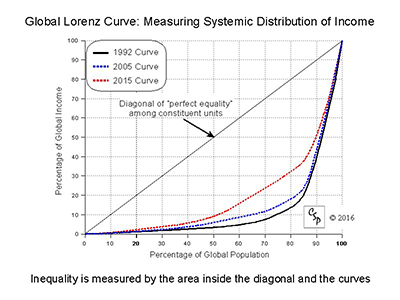

Figure 1: Global System - Income Distribution, 1992, 2005, and 2015

Researchers at the Center for Systemic Peace have been monitoring general, global system performance since the Center was established in 1997. Of course, the global system itself is unique. However, our extensive systems analysis strongly suggests that societal-systems at all levels of organization share fundamental systemic attributes, involving both structure and agency. Using macro-comparative methods of "cross-national" and "comparative regionalism" research, we have observed strong and consistent correlations among qualities of conflict, governance, and development in societal-systems. Well-performing societal-systems combine non-violent conflict, democratic governance, and highly productive and self-sustaining development. Poor-performing societal systems are characterized by high levels of violent conflict, weak autocratic or anocratic governance, and low productivity and income.

Plotting the distribution of income among constituent units in a societal-system, using a Lorenz curve, provides a single, and in this case stark but improving, portrayal of the prospects of the system for conflict management in the near term. The area inside the "diagonal of equality" and the "curve of inequality" measures the extent of the unequal distribution of income. The curve in Figure 1 reveals that the top 20% of the world's population receives over 80% of the income, an almost perfect inequality of income distribution and an enormous challenge for global governance, conflict management, and globalization (such highly unequal systems tend toward autocratic/forceful forms of conflict management). Slight improvement in 2005 income distribution over 1992 is accounted largely by the emergence of China in the global market. The marked improvement in the 2015 curve begins to show the systemic benefits of globalization as middle income countries, such as Brazil, China, and South Africa start to close the income gap.

To view a more detailed analysis of the

"Global System and Comparative Regionalism," including regional income distribution profiles,

See also, chapter six in Third World War.

-

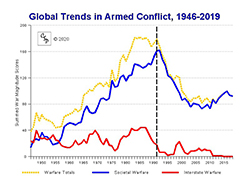

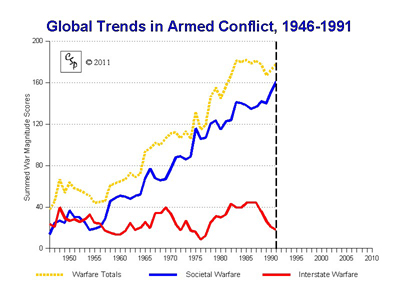

Figure 2: Global Trends in Armed Conflict, 1946-1991

The red-line charts the trend in general level of interstate war in the global system; that measure includes all wars of independence from the Colonial System and has remained fairly constant at a low level through the Cold War period. We can see from the graph that the UN System, that was designed to regulate inter-state war, has been reasonably effective in providing inter-state security. However, the UN System has not been effective in regulating societal (or civil) warfare. The level of societal warfare increased dramatically and continuously through the Cold War period. Separate research indicates that the increasing level of societal war results from the protractedness of societal wars during this period and not from a substantial increase in the numbers of new wars. Click here for a brief description of the methodology used to create the trend graph.

-

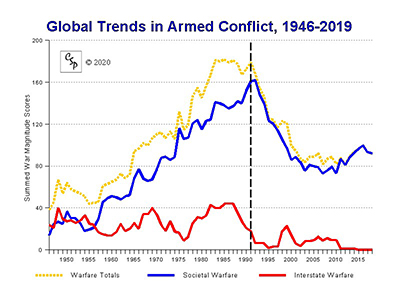

Figure 3: Global Trends in Armed Conflict, 1946-2019

The end of the Cold War, marked by the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, had an equally dramatic effect on the general level of armed conflict in the global system. The levels of both interstate and societal warfare declined dramatically through the 1990s and this trend continues to the early 2000s, falling over 60% from their peak levels. The trend appears to have changed in the mid-2000s back to an increasing trajectory. Most of the increase over the past fifteen years has been in Muslim countries and concentrated in the North Africa and Middle East (MENA) region (see figure 19 below). The global trend in interstate warfare appears to be diminishing across the contemporary period with no interstate wars recorded for the first time in 2015. This positive trend needs to be considered in the context of changing technologies: with the increasing sophistication of aerial weaponry, interstate warfare can be projected from remote locations and deaths resulting from such action are largely avoided, keeping those actions under the 500 death threshold for inclusion.

To review the complete listing, "Major Episodes of Political Violence, 1946-2019," used to construct the warfare trends, click here.

You may also view regional sub-system trends graphs by clicking here or politically-relevant regional trends by clicking here.

-

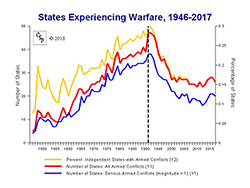

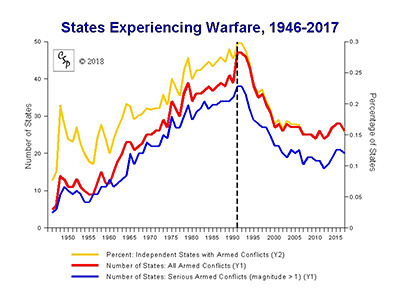

Figure 4: States Experiencing Warfare: 1946-2017

A second look at the global trend in armed conflict comes from charting the number of states experiencing any form of warfare in each year. Figure 4 charts three different metrics but the trends that emerge remain consistent with those charted in Figure 3.

At the peak in 1992, nearly thirty percent of the countries in the world were experiencing some form of major political violence (29.9%). This percentage of the world's independent states with major episodes of political violence (with total population greater than 500,000 in 2017) dropped by more than one-half since the end of the cold war, registering at just over 13% in 2010; the percentage of states experiencing warfare has leveled off in the 2000s.

Increasing violence in the Middle East and the Sahel region of Africa (MENA region) has contributed to a leveling of the post-Cold War trend since the beginning of the "Global War on Terror" in the early 2000s.

-

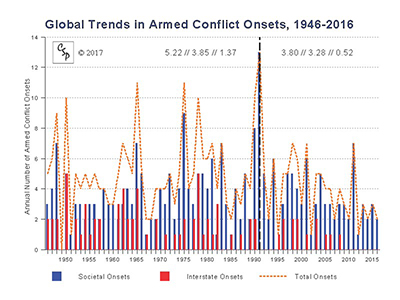

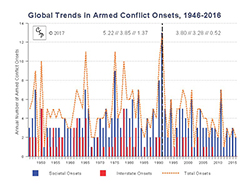

Figure 5: Global Trends in Armed Conflict Onsets, 1946-2016

A third perspective on the global trend in armed conflict focuses on the annual numbers of onsets of new wars in the global system to examine their frequency and regularity and whether there have been marked changes in those factors over time. Figure 5 charts three additional metrics: 1) number of interstate war onsets (red bars), 2) number of societal war onsets (blue bars), and 3) total onsets (orange dashed-line). The number of new war onsets fluctuates between zero and thirteen per year and the number of new societal wars is generally higher than new interstate wars. There is a peak in new societal war onsets that coincides with the end of the Cold War (1990 and 1991), however, the average frequency of societal war onsets does not appear to have changed much across the shift from Cold War to post-Cold War periods. The average rate of onset for societal wars changes slightly: from 3.85 to 3.28 per year. On the other hand, the average rate of onset for interstate wars seems to have fallen to almost a third of the rate during the Cold War period (from 1.37 to 0.52 per year); this brings down the average number of (total) war onsets from 5.22 per year during the Cold War to 3.80 per year in the post-Cold War period. There have been no interstate war onsets for the past eight years.

-

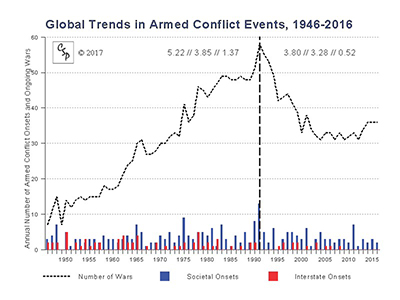

Figure 6: Global Trends in Armed Conflict Events, 1946-2016

Whereas Figure 4 looks at the annual number of states directly affected by (any number of) armed conflicts, Figure 6 charts the annual number of ongoing armed conflicts in the global system (overlaid on the onset trend data from Figure 5). This perspective on global trends in armed conflict largely parallels the charted trends in war magnitude and number of states affected, however, this measure shows evidence that the downward global trend in armed conflicts has leveled off in the early years of the 21st Century, indicating that recent wars are increasing in intensity (driving summed magnitude scores upward, see figure 3). In early 2017, there are 28 states directly affected by ongoing wars (36 wars total, up from 27 at the end of 2002). Of these 28 states, nearly half (13) are affected by protracted wars, that is, armed conflicts persisting for more than ten years. These protracted societal conflicts include Afghanistan (36 years), Colombia (39), D.R.Congo (22), India (62), Iraq (34), Israel (49), Myanmar (66), Nigeria (17), Pakistan (17), Philippines (42), Somalia (26), Sudan (31), and Turkey (30); Sri Lanka ended its protracted war with ethnic-Tamil separatists in 2009 and Colombia has recently signed a peace treaty in hopes of ending its civil war. The remaining protracted wars continue to defy concerted efforts to gain settlement or resolution. On average, during the contemporary period, interstate wars lasted about 3 years; civil wars lasted just over 5 years; and ethnic wars lasted nearly 10 years.

-

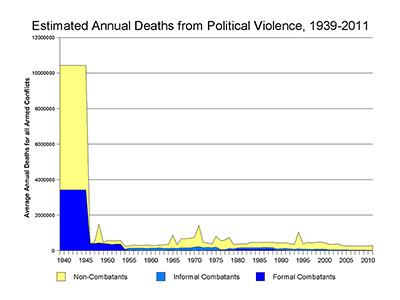

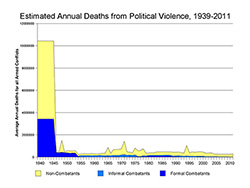

Figure 7: Estimated Annual Deaths from Political Violence, 1939-2011

Figure 7 takes a step back in time to add perspective to the contemporary period and what we have termed the "Third World War" by comparing it to the almost inconceivable magnitude of devastation that occurred during the Second World War. Modern, professional warfare conducted by the full coterie of the world's most technologically and economically advanced countries has been estimated to have resulted in the deaths of about 24 million formal combatants and nearly 50 million non-combatants over the seven year duration of the Second World War (the graph simply averages the estimated total global deaths of the war over the seven-year span). We know of no systematic estimates of the numbers of "informal combatants" killed during the war so we assume that these deaths are included with the noncombatant estimates. The efforts of "partisan" fighters to target authorities and weaken and disrupt war support activities behind enemy lines were significant and may account for up to ten percent of the noncombatant death figures but we can only speculate of the real numbers of fighters killed as a result of local rebellions. On the Eastern European and Eastern Asian fronts, informal fighters fought along side formal military units and are probably included in the "formal combatant" death estimates as these areas were the least "formally developed" regions involved in the warfare and experienced the highest total numbers of deaths (e.g., China and the Soviet Union).

-

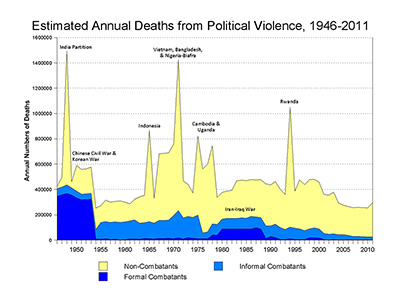

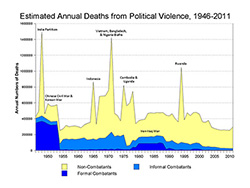

Figure 8: Estimated Annual Deaths from Political Violence, 1946-2011

Figure 8 removes the Second World War period from the global trend graph so we can focus on changes that have occurred during the contemporary period. We have to assume that the Second World War was a "watershed" event in modern global development that marks the end of warfare among the world's most advanced countries because, if its not such a "watershed event" and given the ever increasing technological and economic capacities of the world's most developed countries, the next global war will mark the end of human civilization. Contemporary warfare trends certainly display evidence that "formal" (or classic) warfare between states is no longer the dominant form of political violence and may even be "managed" by the conventions and institutions that have come to characterize the "United Nations System." Unfortunately, the observed diminution of formal warfare may be an artifact of the first two World War experiences that can be summed up by the adage "once burnt, twice shy." The experience of warfare is known to dampen enthusiasm for that kind of activity in directly affected populations, at least temporarily. A second adage warning us that "war is most seductive to those with no experience of it" should serve to as a reminder to maintain vigilance. Indeed, many of the regions most affected by warfare during the contemporary period are those which were not directly affected by the earlier World Wars. The full impact of "amateur warfare" in the world's lesser developed countries is difficult to assess because it affects highly vulnerable populations in economically poor and technologically backward regions.

The "Third World War" appears to be characterized by periodic outbursts (spikes) of extreme violence; the principal victims appear to be civilians caught up in the existential struggle to survive under challenging circumstances (87% of estimated annual deaths from political violence since the year 2000). It appears that ever smaller numbers of combatants are losing their lives while the societal-system devastation of warfare remains a continual problem.

-

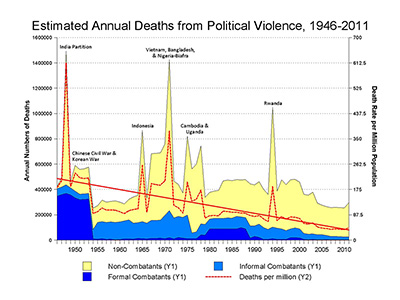

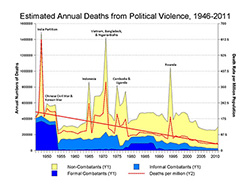

Figure 9: Estimated Annual Deaths from Political Violence, 1946-2011 (Rate per million population)

Figure 9 adds a slightly more encouraging perspective to the global trend graph of deaths from political violence by examining the trend as a "death rate" rather than simply charting annual numbers of deaths over time. The world's population is growing relatively rapidly while the numbers of deaths during the contemporary period seem to remain fairly constant (except for the periodic spikes). Once we control for global population growth (red dashed line), we can see that the annual "death rate per million population" from political violence is diminishing over the contemporary period (red solid line), from about 215 per million in 1946 to about 35 per million in 2011. The spikes of violence also appear to be happening less frequently (or this is an illusion and the pattern simply indicates that we are due for another spike). In any case, we can not discount the importance of global development and the due diligence of conflict management and prevention efforts; they are our best hope for a better future.

-

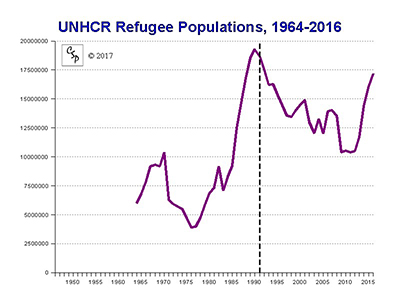

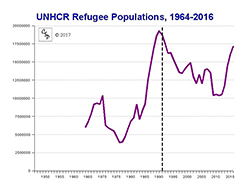

Figure 10: UNHCR Refugee Populations, 1964-2016

Figure 10 graphs the annual numbers of transnational refugees for all countries, as reported in the United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (USCRI) annual series World Refugee Survey (the most recent edition, 2009, counts refugee populations as of December 31, 2008). Information on global refugee populations is now published annually by the UNHCR in its Global Trends and Statistical Yearbook series. The reasons explaining the enormous increase in the global refugee population beginning in the mid-1980s is difficult to ascertain, although this increase coincides with the long and steady increase in global warfare during the Cold War period (see figure 3, above). There are surely some reporting issues involved but it appears that the magnitude of the increase may be best explained by a confluence of at least four factors: 1) armed conflicts are more likely to be located in poorer countries; 2) the protractedness of societal conflicts progressively challenges the ability of societies to meet and maintain basic needs production; 3) there is a breakdown in distinctions between combatants and non-combatant populations; and 4) there is a tremendous expansion in the numbers and capacities of non-governmental organizations willing to provide humanitarian assistance to war-torn societies. The decline in the global refugee trend immediately following the end of the Cold War also parallels the decline in global warfare after 1991. Since about 2011, the numbers of refugees has increased dramatically once again.

-

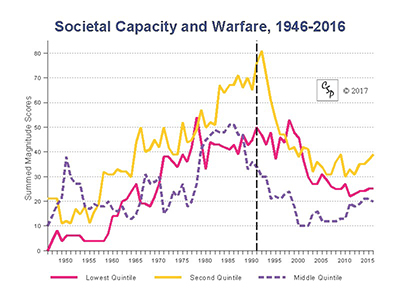

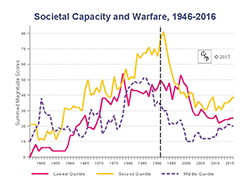

Figure 11: Societal Capacity and Warfare, 1946-2016 - The Poorer Countries

Figure 11 presents a comparison of warfare trends in the bottom three quintiles countries, based on state economic capacity (GDP/capita) across the study period. Whereas the "long peace" enjoyed by the world's more affluent states is strikingly evident in Figure 12, below, this figure shows that war became concentrated in the bottom two quintiles of states (i.e., the weakest 40 percent). The poorer countries account for a disproportionate share of the global warfare totals across the period. Warfare totals for the bottom three quintiles of states increase steadily through the contemporary period, reaching their peaks in the 1980s and early 1990s. The poorest quintiles each show distinctive profiles and high levels of armed conflict that increase during the Cold War period and drop sharply around the end of the Cold War (marked by the vertical line). At the peak, over half of the poorer countries are consumed by societal warfare.

What distinguishes the lowest quintile is the persistence of high levels of warfare through the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. This may be explained simply by pointing out that they have more fragile societal-systems, more vulnerable populations, and lower capacities for properly managing conflicts than countries in the higher quintiles. This helps to explain the perceived dramatic increase in serious humanitarian crises in the 1990s and, now, again in the 2010s. Pervasive violence and societal system breakdowns in poorly developed countries inevitably lead to humanitarian crises and disasters without substantial and sustained, constructive assistance from external sources and the poorest countries have trouble attracting such assistance, particularly over the long periods of time needed for stabilization and rejuvenation.

Comparing these trends with similar plots based on state economic capacity in the early years of the study period (our prior method) shows evidence of the degrading effects of pervasive warfare on economic capacity: armed conflict tends to occur in poorer countries and tends to keep them poor and make them poorer still over time.

-

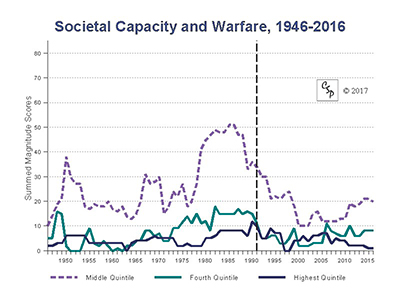

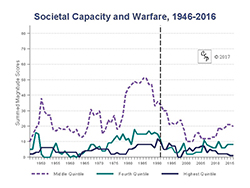

Figure 12: Societal Capacity and Warfare, 1946-2016 - The Richer Countries

Figure 12 displays the warfare totals for the top three quintiles of state capacity (the third quintile is included to facilitate comparison with the bottom quintiles presented in Figure 8). Readily apparent are the much lower levels of warfare in the upper quintiles. Especially fortunate are the states in the upper quintile where little or no serious political violence takes place for the entire time span; their involvement in armed conflicts are mainly in the role of "police action" in foreign wars, particularly in "internationalized civil wars."

Of course, this good fortune at home, coupled with the complexities of foreign interventions, go a long way to explaining the difficulty of mobilizing "political will" in the richer countries to recognize, let alone meaningfully address, the complex problems associated with armed conflicts in the poorer countries.

-

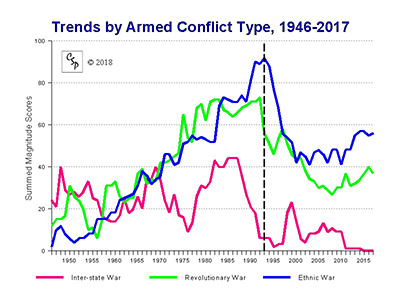

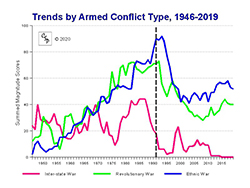

Figure 13: Trends by Conflict Type, 1946-2019

Ethnic warfare became the hot topic in the years immediately following the end of the Cold War as a virtual cornucopia of these seemingly intractable (and previously "invisible") social identity conflicts exploded onto the world scene and captured public and policy eyes. In order to more fully assess the impact and importance of ethnic conflict in the post-Cold War period it is helpful to place that particular type of societal conflict into its global systemic context. Figure 13 compares trends for three distinct types of warfare, ethnic, revolutionary, and inter-state (including "extra-systemic" or anti-colonial wars). The perceived "sudden rise" in ethnic wars in the 1990s appears to be a curious outcropping of more general, systemic changes. After a substantial drop in the 1990s, the global trend in ethnic wars leveled off in the 2000s and has begun to increase somewhat in the 2010s. Revolutionary wars have also increased in the past ten years.

As the Cold War ideologies wax and wane in the late 1980s, the support they lend to both inter-state and revolutionary intra-state wars is eroded and those types of warfare greatly diminish. The ethnic war trend, which had previously paralleled the trend of revolutionary war, continues to rise through the late 1980s and early 1990s as separatists and other political entrepreneurs attempt to take advantage of the vast changes in political arrangements that accompanied the transformation of the post-Cold War world system. Ethnic wars stand out like a "sore thumb" in the 1990s' security environment. Also, notice that the long-term trend in ethnic warfare increases relatively smoothly as compared to the other warfare trends.

As the goals of social identity (ethnic) conflicts are suffused with non-negotiable symbolic issues, these conflicts are less susceptible to settlement or resolution by warfare and, so, tend to persist and/or re-emerge over time. Also, notice that the sharply decreasing trend in ethnic warfare of the 1990s has leveled off since the turn of the century and may be increasing once again.

-

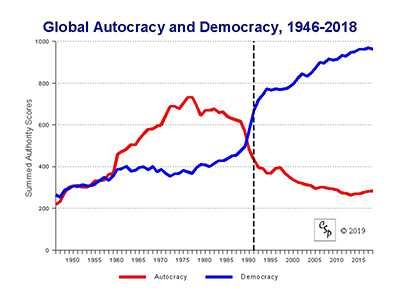

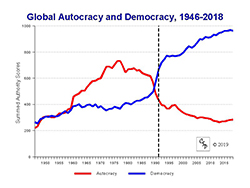

Figure 14: Global Democracy and Autocracy, 1946-2018

Figure 14 simply sums Polity IV scores of institutional authority for democracy and autocracy for each independent state for each year; Polity IV special codes (-66, -77, -88) are treated as missing data here. In the Polity IV data each country is given annual scores (10-point scales) on each of two basic types of regime authority. Although the two types of authority are opposing, many countries exhibit mixed authority traits (i.e., they have middling values on each scale).

The graph in Figure 14 shows global changes in total "units of democracy" in contrast to total "units of autocracy" in the global system.

-

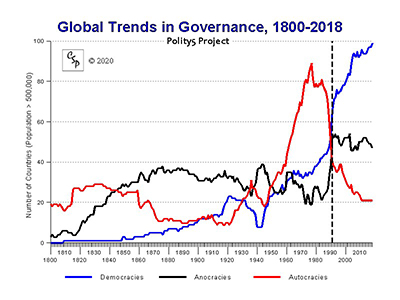

Figure 15: Global Trends in Governance, 1800-2018

Figure 15 provides a long-term assessment of global trends in the qualities of governance, covering the period from 1800 to 2018. We can see that the independent countries of the world during the 19th century numbered only 22 in 1800 and grew to 55 by 1850; regimes by the middle of the 19th century were about evenly split between fully institutionalized monarchies (i.e., autocracies) and newly emerging countries which were mainly mixed or "incoherent" authority regimes (i.e., anocracies). The numbers of democratic regimes can be seen to increase very slowly during the latter half of the 19th century through the end of First World War, when there was a relatively rapid increase in their number. This increase in the number of democracies following the First World War was reversed during the Great Depression and undone by the onset of the Second World War; this time period marks the only reversal in the steady increase of democratic governance since 1800.

The end of the Second World War is characterized by an enormous increase in the number of newly independent countries brought about by the collapse of the European Colonial System; these newly emerging countries, although initially split among autocratic, anocratic, and democratic regimes, quickly adopted mainly autocratic forms of governance. The end of the Cold War period in the late 1980s marks the collapse of the "new autocratic regimes" and a transformation of old autocratic regimes to more democratic forms.

-

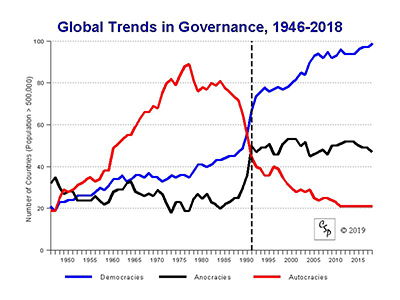

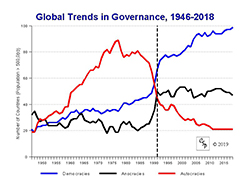

Figure 16: Global Trends in Governance, 1946-2018

Figure 16 provides a second perspective on the global trend in governance. This graph was originally designed for inclusion in the UN Secretary General's Millennium Report. It uses Polity IV data on institutional authority for all independent states in the world from 1946-2018. The trend lines denote the annual number of states with each of three general authority patterns: democracy, autocracy, and anocracy. The Polity score combines the separate Autocracy and Democracy scores mentioned above into a single indicator of governance, ranging from -10 (fully institutionalized autocracy) to +10 (fully institutionalized democracy). In this rendition, Democracies are designated by having a Polity score of +6 or greater; Autocratic states have a combined score of -6 or less. Anocracies are a middling category of states with incoherent or inconsistent authority patterns: partly liberal, partly authoritarian (i.e., -5 to +5 on the Polity scale). The Anocracy category also includes countries with any of the three special Polity codes: -66 (interruption), -77 (interregnum), and -88 (transition). Anocracies are relatively vulnerable and volatile states that often lack effective institutions and/or the capacities to establish and maintain social order.

-

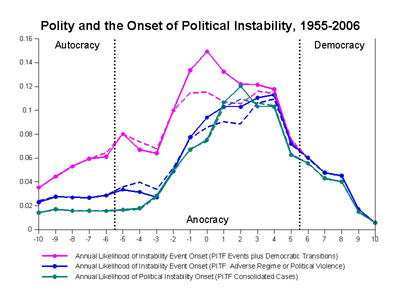

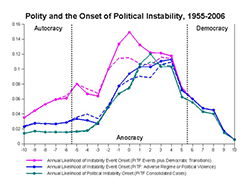

Figure 17: Annual Likelihood of Political Instability by Polity Score, 1955-2006

Figure 17 charts the relationship between a regime's Polity score and the likelihood of onset of a political instability event. The Political Instability Task Force (PITF) identifies four categories of instability events: 1) an "adverse regime change" (defined by a sudden five point or more drop in a state's Polity score or a collapse of central authority); 2) a "revolutionary war" pitting a non-state challenger against state forces and resulting in 1000 or more "battle-related deaths"; 3) an "ethnic war" pitting a distinct ethnic group against the state, also, resulting in 1000 deaths of more; and 4) a genocide or politicide defined as the deliberate use of lethal violence by state agents against members of a distinct social or political group by state. CSP includes a fifth category of instability event, a "major democratic transition," identified by the weakening or reform of autocratic authority and defined by a sudden five point or more drop in a state's (Polity) Autocracy score.

Figure 17, then, plots the likelihood of the onset of an instability event for each value along the 21-point Polity scale; it further demarcates the three categories of regime type on the scale. The magenta line plots the annual likelihood for an onset from any of the full, five categories described above (including democratic transitions); the dark blue line plots the annual likelihood of onset for any of the four PITF categories. The teal line plots the annual likelihood of the onset of a period of political instability (i.e., a "consolidated case" within which there may be one or more instability events covering a continuous period of time during which there is never more than a five-year span of political stability); onsets for this set of cases can only occur in a year of political stability, so, the likelihood for this set is determined by a reduced set of "stability years." Regardless of the definition of "instability," Anocracies (-5 to +5 on the Polity score) clearly have the greatest risk of instability, while autocracies and unconsolidated democracies have a lesser, yet still substantial, risk.

Fully institutionalized democracies (+10 on the Polity scale) are associated with the lowest risk of onset of a political instability event, by far. By discounting political instability "triggered" by democratic transitions in autocratic regimes, one can get the impression that autocracies are similarly, or even more, stable when compared with democracies. In fact, autocracies are seven to ten times more likely to experience an onset of instability compared with "fully institutionalized democracies" (+10 on the Polity scale).

Note that these plots are smoothed by using three-category averages; this reflects the estimated error in the Polity measure (+/-1 point); dashed lines plot onsets using the POLITY2 score which assigns standard scores to -88 and -77 cases.

-

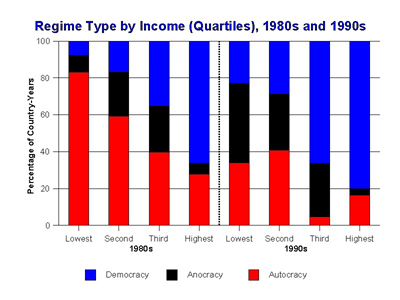

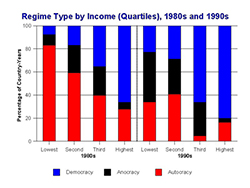

Figure 18: Regime Type by Income Quartiles - Comparing the 1980s and 1990s

Whereas Figures 14-16, above, clearly show the evidence of a "third wave" of democratization that coincides with the end of the Cold War and the general decline in global armed conflict (Figure 3), Figure 16 also shows a nearly three-fold increase in the numbers of "anocratic" (hybrid) authority regimes. Our research and, particularly, the PITF research have shown that anocratic regimes have the highest risk of political instability (Figure 17). The simultaneous and dramatic increase in anocratic regimes in the global system and decrease in global armed conflict, especially in light of the unchanged rate of onset for armed conflict events, appears to present a paradox, or at least a conundrum. Anocracies seem to have a lower, or slower, risk of instability in the post-Cold War world.

Figure 18, here, reveals another piece in the puzzle by comparing the general relationship between per capita income and regime type for the two decades just prior to and after the end of the Cold War (i.e., the 1980s, left side, and 1990s, right side). The linear relationship between societal-system development (measured by GDP/capita) and mode of governance has broken down in the later period and countries in the lower three quartiles of income appear to be having trouble establishing and consolidating democratic authority. Premature democratization in poorer countries poses unique challenges for the global system.

-

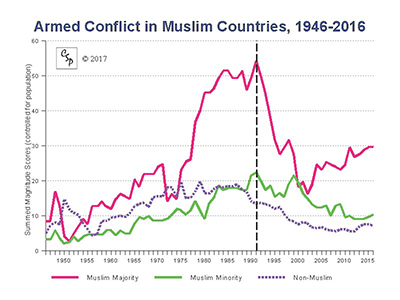

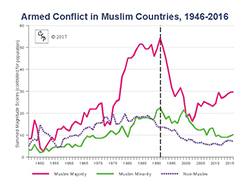

Figure 19: Armed Conflict in Muslim Countries, 1946-2016

With the global "War on Terrorism" transforming the Muslim World to a battle against a network of forces comprising an "Islamic State," the increasing extremist violence of the "Arab Fall" succeedes the budding aspirations of the "Arab Spring." The question arises whether the general trend in armed conflict in the Muslim-majority countries differs from the trends for Muslim-minority and non-Muslim countries of the world. Figure 19 presents a graphic comparison of armed conflict trends in three subsets of the world's countries: 1) countries with Muslim majorities (red line); 2) countries with substantial Muslim minorities (greater than 5% of the population; green line); and 3) non-Muslim countries (purple dotted line).

The Muslim-Majority Countries subset account for a little less than one-fifth the world's population in 2016 (19.1%). The Non-Muslim countries include most of the Advanced Industrial Countries of Western Europe, North America, and Oceania (except France, which has a large Muslim minority); these countries experienced very little armed conflict on their territory during the contemporary period but were involved in several, major military interventions (such as Afghanistan, Algeria, Vietnam, and Iraq). The Non-Muslim Countries subset accounts for nearly half the world population in 2016 (48.4%). The Muslim-Minority Countries account for about one-third of the world population (32.5%).

When the global shares of global armed conflict for each of these three subsets is controlled for their relative share of the world population, a fairly stark reality is revealed that helps to account for the perception we, as observers, have of the extreme social conflict and intense political violence that has engulfed the Muslim-Majority Countries since the 1970s. Each of the three groupings demonstrates similar trajectories until the mid-1970s, then the Muslim-Majority Countries experience a steep increase and far surpass the armed conflict levels of other two subsets of countries. Levels of armed conflict decreased substantially for all three subsets around the end of the Cold War (here marked as 1991), beginning with the Non-Muslim Countries in the late 1980s. Armed Conflict in the Muslim-Majority Countries dropped with the end of the Cold War just as steeply as it had arisen following the 1973 Oil Embargo. Armed Conflict decreased in the Muslim-Minority Countries in the first years of the new millennia. Armed conlict in Muslim-Majority Countries has increased sharply once again since the US invasion of Iraq in 2003.

This perspective on global trends in armed conflict really accentuates, but does not explain, the unique experience and challenges facing the world's Muslim countries. Given the shear magnitude of political violence affecting this subset of the global population, one can begin to grasp the extent of the trauma that the affected population will carry forward and the basis for and genesis of the extreme behaviors that have come to characterize our perceptions of this population. What may be of greatest concern going forward is the increasing concentration of global armed conflict in the Muslim-Majority Countries, which are, themselves, concentrated spatially in North Africa and the Middle East. Although the level of armed conflict in 2016 is only about 60% of the 1991 peak, the magnitude is still rising and is taking place in a region that has not had time to recover from the decimation represented by the previous peak.

-

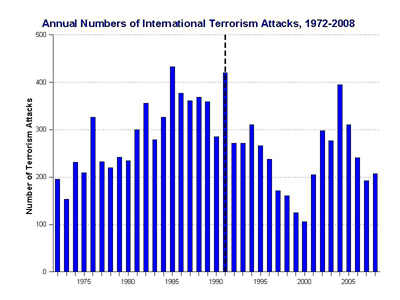

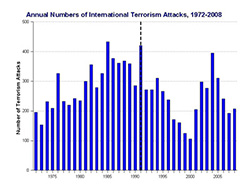

Figure 20: Annual Numbers of International Terrorism Attacks, 1972-2008

Figures 20 and 21 draw upon data provided by the RAND Database of Worldwide Terrorism Incidents (RDWTI; www.rand.org/nsrd/projects/terrorism-incidents.html) in order to chart contemporary trends in international terrorism. The RDWTI was one of two comprehensive compilations of international terrorism events; the other being the ITERATE database. More recently, the START project at the University of Maryland, College Park, has built on these efforts and compiled their own data base on terrorism events worldwide.

Figure 20 shows a general decrease in the numbers of attacks during the decade following the end of the Cold War and, except for the spike in 1991, a fairly steady decline from 1985 through 2000; this trend is corroborated by similar analyses of the ITERATE data. The incidence of attacks increases substantially in the post-9/11 period but remains generally lower than the rate during the peak of such activity in the 1980s. RAND provides the following definitions of these events:

Terrorism defined: "For the purposes of data, terrorism is defined by the nature of the act, not by the identity of the perpetrators or the nature of the cause. Terrorism is violence, or the threat of violence, calculated to create an atmosphere of fear and alarm. These acts are designed to coerce others into actions they would not otherwise undertake, or refrain from actions they desired to take. All terrorist acts are crimes. Many would also be violation of the rules of war if a state of war existed. This violence or threat of violence is generally directed against civilian targets. The motives of all terrorists are political, and terrorist actions are generally carried out in a way that will achieve maximum publicity. Unlike other criminal acts, terrorists often claim credit for their acts. Finally, terrorist acts are intended to produce effects beyond the immediate physical damage of the cause, having long-term psychological repercussions on a particular target audience.

The fear created by terrorists may be intended to cause people to exaggerate the strengths of the terrorist and the importance of the cause, to provoke governmental overreaction, to discourage dissent, or simply to intimidate and thereby enforce compliance with their demands."

International Terrorism defined: "Incidents in which terrorists go abroad to strike their targets, select domestic targets associated with a foreign state, or create an international incident by attacking airline passengers, personnel or equipment."

-

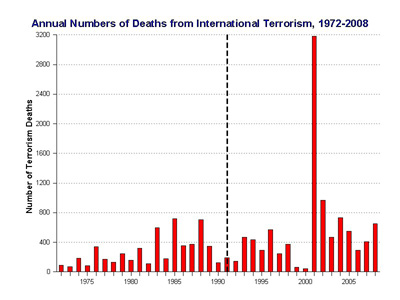

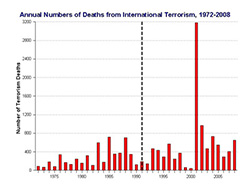

Figure 21: Annual Numbers of Deaths from International Terrorism, 1972-2008

Figure 21, then, uses the RAND Database of Worldwide Terrorism Incidents (RDWTI) to chart the annual numbers of deaths that resulted from the attacks charted in Figure 20 above. One can immediately see the extraordinary anomaly represented by the 9/11 attacks on the USA; these four attacks in New York City, Washington DC, and Somerset County PA account for 2,982 deaths (all but 202 of the death total in 2001).

The average number of deaths in the sixteen years prior to the peak in 2001 (1985-2000) is 341; the average for the seven years following 2001 is 582, nearly sixty percent greater than the average for the earlier period. Still, these annual totals are extremely low when compared to other forms of political or criminal violence.

The CSP study on "Global Terrorism: An Overview and Analysis" (CSP Virtual Library) proposes that "international terrorism" accounts for less than ten percent of global terrorism since 1990; the vast majority of global terrorism is local, or national, terrorism. The rates for international terrorism are further qualified by tremendous increases in international activity that have accompanied globalization and the post-Cold War expansion of the free market system.

-

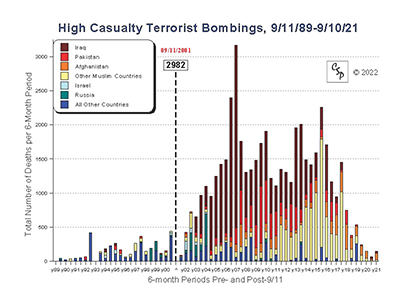

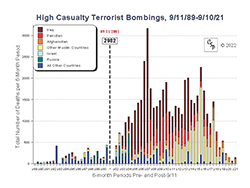

Figure 22: High Casualty Terrorist Bombings, 9/11/1989-9/10/2021

Figure 22 provides a unique examination of recent, global trends in "high casualty terrorist bombings" (HCTB; that is, bombings that target noncombatants and result in 15 or more deaths); each bar charts the total number of HCTB deaths in successive six-month periods pre- and post-9/11/2001. While the frequency and lethality of "international terrorism" does not appear to have increased much in recent years and, in any case, remains at extremely low levels when compared with any other form of political or criminal violence, the tactical use of "low-tech, smart bombs" (mainly car bombs and suicide bombers) against "soft targets" (political and civilian targets) increased dramatically following the 9/11 attacks (in which 2,982 people were killed). However, most of the "high profile" terrorist attacks since the peak in 2007 have been confined to a handful of Muslim-majority localities: Iraq, Pakistan, and Afghanistan and, since 2011, other Muslim-majority areas such as Somalia, Syria, Yemen, and northern Nigeria.

While the rise of the "super-empowered terrorist" as an innovation in tactical or criminal violence was certainly disturbing, the evidence shows that it remains an extreme and relatively isolated event. HCTB attacks have killed more than 48,452 people since 9/11 compared with 3,691 people killed during the twelve-year period prior to 9/11; the greatest number of post-9/11 HCTB killings have taken place in Iraq (21,202; 43.9%) although there have been no recorded incidents in Iraq for more than two years. By way of comparison, major episodes of political violence have resulted in an estimated 3.5 million deaths during the post-9/11 period. While HCTB attacks peaked dramatically between September 2006 and September 2007, they remained at a fairly constant level from 2004 through 2017 at about 1300-1500 per six-month period with sporadic peaks around the 2000 death level. HCTB attacks peaked in Iraq in September 2007 (2,677 deaths in the preceding 6-month period), in Pakistan in March 2009 (836 deaths), and in Other Muslim Countries in March 2016 (1,582 deaths). Remarkably, HCTB attacks have diminished sharply over the past three 6-month periods, falling to their lowest level since March 2002.

To view a PDF copy of the HCTB events list, click here.

Note: Armed assaults on non-combatant targets that rely mainly on firearms or other hand-held weapons are not included in this compilation. The numbers of deaths and "disappearances" attributed to such "death squad" activities often far surpasses the death totals of the highly visible HCTB events recorded here (e.g., c9000 "criminals" have been killed in the Philippines since 2016). There is also a strong association between lethal repression by state agents and terrorist violence by non-state actors.

-

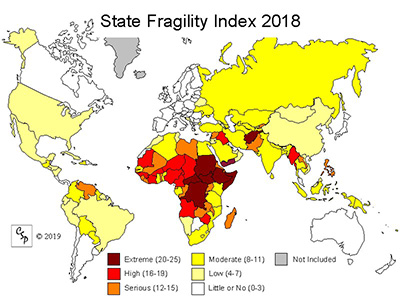

Figure 23: Global Distribution of State Fragility 2017

Effective conflict management and, therefore, systemic peace result from a fundamental congruence between societal-system resilience and the systemic risk factors that would otherwise trigger contention and fuel the escalation to violence. The Global Report series includes a detailed assessment of "state fragility" for each of the world's major countries (with populations greater than 500,000) that comprises a 2x4 matrix of indicators (effectiveness and legitimacy indicators for security, governance, economic, and social dimensions of state performance) rated on a scale of 0 (no fragility) to 3 (high fragility). The economic effectiveness indicator includes an extra "extreme" value (4) identifying countries locked in extreme poverty, defined as GDP/capita less than $500 (constant 2005 US$). These eight indicators are, then, summed to form composite indices of (il)legitimacy and (in)effectiveness; the comprehensive "state fragility index" combines these two key indices.

Figure 23 shows a concentration of extremely, highly, and seriously fragile states in Africa and southern Asia. Fragility in the Western Hemisphere is less severe and concentrated in Central and in north and central South America. We find that there has been steady improvement in general resilience in the global system since 1995 (the global mean score has fallen from 10.85 in 1995 to 9.53 in 2004 and to 7.93 in 2017; the global mean increased to 7.98 in 2018) with similar, absolute improvement in the five non-Western world regions; however, the "resilience gap" has been maintained in relative terms. Improvements attributable to the post-Cold War "peace dividend" have slowed in recent years as warfare in the MENA region has increased; there has been little or no improvement in the Muslim countries in the past five years..

The most substantial improvements are found in the former-Socialist states of eastern Europe; however, improvements in this region have also diminished in the most recent five year period. Global gains are observed for seven of the eight fragility indicators; only "economic legitimacy" shows no improvement since 1995, indicating that there has been no substantive shift away from primary commodities export toward manufactured goods in the world's more fragile states. Gains in effectiveness have outpaced gains in legitimacy. Click on the map at right to compare the 1995, 2005, and 2018 state fragility maps and view two graphs summarizing progress made in reducing state fragility from 1995 to 2015.

Copies of Global Reports 2007, 2008, 2009, 2011, 2014, and 2017

can be found in the Center for Systemic Peace

The State Fragility Matrix for the most current year (2018) is now available; we will release 2019 figures soon.

Click here to view the full listing of 2018 State Fragility scores for 167 countries.

The full, annual State Fragility time-series data (1995-2017)

is available on the INSCR Data Page.

-

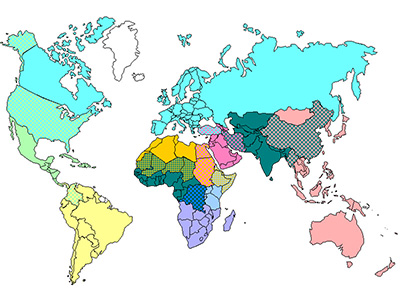

Regional Trends Suite (Systemic Regions):

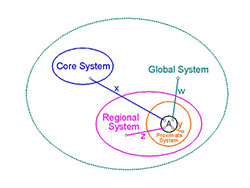

Comparative Regionalism - Income Distribution, Governance, and Warfare, 1946-2006

In Chapter 6 of the book, Third World War, it is argued that much can be learned about complex societal-systems' structures and dynamics by comparing regional sub-systems, as these sub-systems have developed relatively independently within the emerging global system; this macro-comparative methodology was termed "comparative regionalism." In comparing regional systems, strong evidence emerged that conflict, governance, and (human and physical) development qualities of societal-systems are concomitant, meaning that these foundational attributes of societal-systems are fundamentally congruent, such that violent conflict, poor governance, and low or poor development are strongly associated, as are civil conflict, good governance, and sustainable development. Societal-system progression, then, is characterized by congruent, or parallel, trends in these foundational qualities, whether the basic direction of these trends is positive or negative. Systemic incongruence, that is, a situation in which the basic trajectory of one of these foundational qualities diverges from the others, creates a societal dilemma and a political crisis for the system. The state (or proto-state) is charged with regulating system congruence and correcting systemic incongruence; state failure leads to increasing atrophy in complex systems and may eventually lead to system failure.

For a detailed, theoretical examination of the foundational structures and dynamics of complex societal-systems, see the video book, titled Managing Complexity in Modern Societal Systems.

-

Regional Trends Suite (Politically-Relevant Regions):

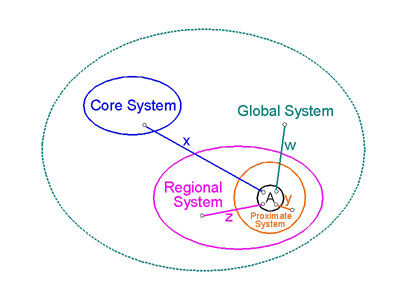

Regional Warfare and Regimes Trends, 1946-2013

Regional warfare and regimes trends, 1946-2013, for ten "politically-relevant" global regions are plotted for comparison. Political relevancy is generally based upon geographical proximity and the regularity of political interactions; relevancy is further conditioned by the general capacity of states to interact: relatively more "powerful" states have a relatively greater capacity to interact both with more states and over greater distances. Interactions by states and among states tend to be concentrated in politically-relevant regions, even though the world's more powerful states can and do interact with states in regions outside their "preferred" region, that is, the region in which they most regularly interact.

Some states "straddle" one or more regions and, so, interact regularly with more than one region; these "straddle states" are included in each of the regions in which they are seen to regularly interact.

The ten "politically-relevant" regions examined and compared in this treatment are the North Atlantic, Central America, South America, North Africa, West Africa, East Africa, South Africa, Middle East, South Central Asia, and East Asia Regions. Island states, such as Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Solomon Islands, and Madagascar, may be considered "politically-remote" and, so, enjoy the luxury of voluntary or conditional political interaction with other states. These states are not included in the regional trends comparisons.

426 Center St. N, Vienna, VA 22180 USA | 202.236.9298 | © CSP 2022